The tragic death of the historian Papiya Ghosh marks the demise of a truly extraordinary scholar, a popular teacher and a dearly loved friend. The manner of her death also exposes the rot that lies beneath our boasts of progress and in our systems of governance.

By Supriya Roychowdhury In Economic And Political Weekly, January 13, 2007.

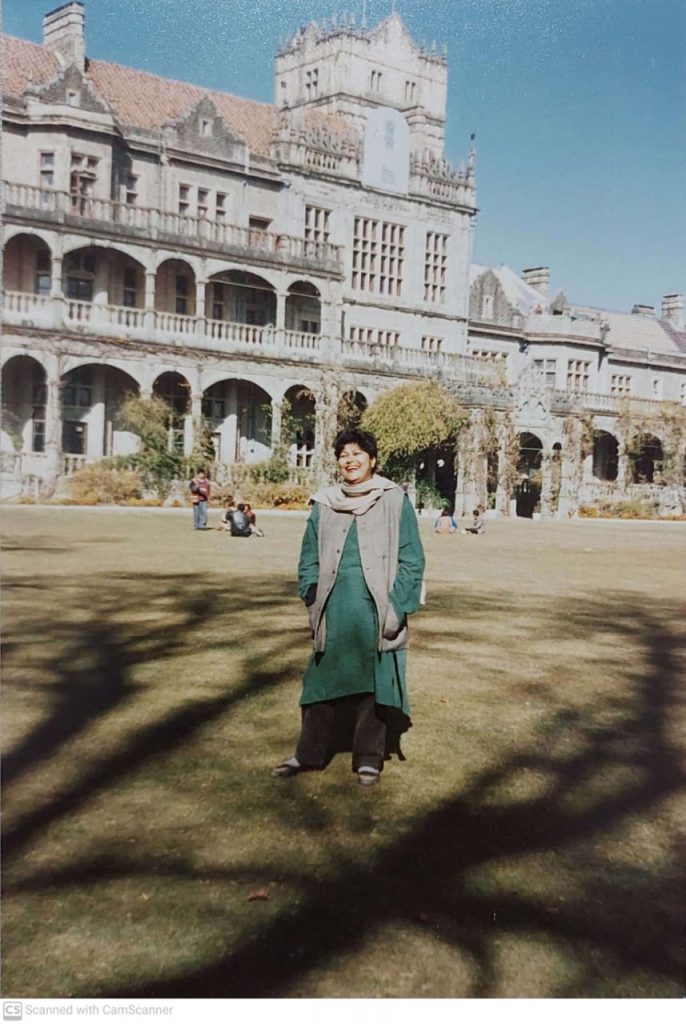

Papiya Ghosh, professor of history, Patna University, died under tragic circumstances on December 3, 2006. Papiya graduated in history from the prestigious Patna Womens’ College in 1975. She then studied at the history department in Delhi University, from where she received her masters, MPhil and PhD degrees. She taught for a few years at the Hindu College in Delhi, and then moved to the Patna Womens’ College. In the early 1990s she joined the postgraduate history department in Patna University. During these years she periodically took time off from teaching to hold two prestigious fellowships, first at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi, and then at the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies, Simla. Papiya had been a Rockerfeller Fellow in Residence at North Carolina State University and at the University of Chicago. She had also been a Fellow of the Indian Council of Historical Research.

Papiya’s research spanned a range that is astonishing in a context where most research in the humanities and social sciences has a tendency to be spatially and temporally limited. Her doctoral dissertation was on the Civil Disobedience movement in Bihar, 1930-34. Her subsequent work, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, was focused on understanding the formation of Bihari Muslim identity in the context of colonial politics. As much of the scholarship on Muslim identity formation has focused on Muslim majority areas like Punjab and Bengal, her research on Bihar, where Muslims were a minority, clearly filled a gap. In later work she chronicled the multiple contestations and challenges to the formation of an exclusivist Muslim League type identity in Bihar, examining the politics and ideology of the Jamiyat-al-ulema-i-hind’s broadly composite nationalism. Papiya’s credentials as a careful historian as also a scholar of imagination were clearly established by this work, published in two papers in the Economic and Social History Review in the early 1990s.

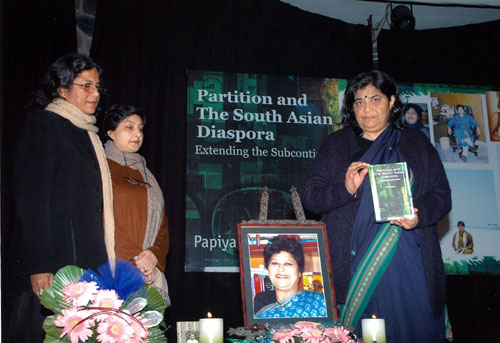

In later years she focused more and more on the history, politics and culture of partition and die south Asian diaspora, presented in several papers, conference presentations, and regular contributions to the journal Refugee Watch. Her book Partition and the South Asian Diaspora: Extending the Subcontinent has been recently published by Routledge (2007). Papiya did not live to see her book in print, released in New Delhi a few weeks after she died.

This book, the culmination of years of meticulous research and writing, is indeed an intellectual tour de force. Much of the scholarship on diaspora has looked at 19th century Indian immigrants to places like Trinidad, Guyana, Surinam and Jamaica, as well as 20th century immigration to the US and Europe. Papiya’s work in this book locates diaspora in the partition experience, but she also pushes the study well beyond the 1940s into the 1970s and 1980s. This research connects the study of two Muhajir formations in East and West Pakistan, that had their beginnings in the aftermath of killings of Muslims in Bihar in late 1946, and then maps, the story of Bihari Muslims displaced from Bangladesh in the aftermath of 1971, located in refugee camps, seeking a temporary base in Bihar, and ultimately seeking asylum in Pakistan, some in the US and Europe. The striking feature of this work is not only that it extends the conceptual horizon of diaspora in time and space, but also anchors itself in the story of a largely ignored and powerless community.

But the conceptual framework is indeed much broader than this. Looking at the post-1980s diasporic experience of Muslims in the US and Europe, she is able to contest standard interpretations that speak of a pan Islamic diaspora as opposed to diasporic Indiahness. Papiya’s work shows that subcontinental diaspora, in the post-1980s, uses partition as a reference point not only in instilling but also in resisting Hindutva. Thus she reconfigures the interface of nation, diaspora and region, to use her own words “even as they reconfigure”. Mapping six decades, and incorporating an astonishing intellectual sweep, this book awaits much more substantive review than has been possible here. Perhaps the most striking aspect of her work was the understanding of history as process, highlighting the tension between choices and patterns, the contingent and the determined. Her most current areas of research were contemporary patriarchies, Ganga-Jamni literature, backward and dalit politics, Bhojpuri cinema and electoral music. At the time of her death, she was completing two volumes on pre- and post-partition Bihar.

Her work stands testimony to her scholarship. Of the countless tributes that have come in after her death, to quote one, her scholarship was indeed silent but stupendous. In a discipline that in India is marked by closed networks, highly self-conscious and exclusive professional fraternities, and, at least until recently, a pronounced Oxbridge/Ivy League bias, the recognition of her research, when it came, was on the basis of her work, and her work alone.

At present the professional/institutional context in the social sciences in India is defined to some extent by the marginali-sation of regional universities and the concentration of resources, connectedness, honour and power at the centre, i e, New Delhi. Papiya had the added disadvantage of being in a regional space/university that has long been on the decline. She developed a somewhat unique professional persona whereby she straddled different professional worlds with great ease. A frequently seen figure at the India International Centre, New Delhi, and at national and international conferences, her professional profile and life placed her well beyond the boundaries of Patna, while her research and teaching remained firmly anchored in the state in which she was born and where she so tragically lost her life.

As a teacher she indeed surpassed herself. As many former and present students have written in the last few weeks, she set for herself the highest standards in the classroom, and expected the same of her students. In an era where research, projects, funding searches, foreign travelling have pushed teaching, for most academics, very much to the back burner, Papiya maintained an unshakeable commitment to the classroom, amongst her many accomplishments.

Papiya, the Friend

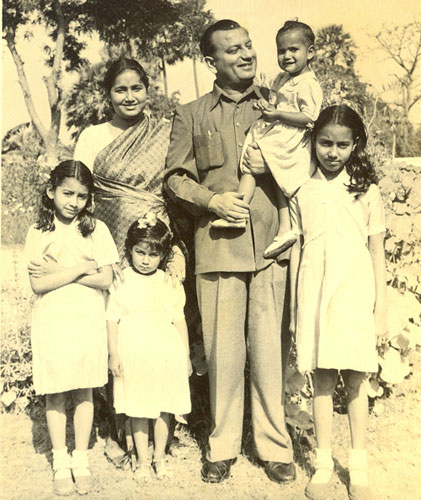

Beyond all this, was Papiya, the friend, with the extraordinary capacity for warmth that won her a place in the hearts of al most all whom she met, across all divides. I met Papiya in Delhi University where I was doing an MPhil, and she had returned for some months to complete writing her doctoral dissertation. This was in 1983. Papiya’s room in the first floor of the South Block, in the PG women’s hostel in Delhi University, was almost an institutionalised space for much lively ‘adda’, before and after dinner. Some were doing their MA, others MPhil and PhD. As many in that cohort would remember, one on one interactions with her became the basis of many deeply rooted friendships that were sustained over the next almost 25 years. After that one year, we all went our different ways, each in a space of struggle with career, relationships, marriage, children, balancing opposed needs, demands, norms, institutions. It was life. One could talk to Papiya always, about anything. She had the uncanny ability to highlight your flaw or weakness, briefly, sometimes almost wordlessly, without being judgmental.

But above all this was indeed her overwhelming interest in a person, the capacity to listen, for deep sympathy, which extended really beyond the individual to her understanding of the human condition itself. It was this unusual quality of being able to negotiate herself between individual affection and a universal warmth, that made her ah indispensable anchor in many of our lives for the last so many years. She had the capacity to perceive a friend from very close, and from very far. The large circle of persons, with whom she connected so closely, could only have been possible with that combination of nearness and distance that she combined so effectively.

The uniqueness of her personality perhaps-went beyond this, to a rock solid bed of courage and humour. Her life was full, with research and teaching, travel and friendships, family. Beneath all this was the predictable struggle, with a declining city administration and a thoughtless university bureaucracy, sometimes with ill health, perhaps with occasional loneliness. But she took every thing on, with a combination of sardonic humour and a self-confidence that did not wait for anyone. Her every day life represented an enviable narrative in independence.

One remembers her joyous appreciation of things beautiful, be it a moving film, an Urdu poem, a song or a painting, of good food and wine, her sudden, hearty laugh, and the softness of her smile that started from her eyes. Again, in the many tributes that have come in since her death, so many have remembered her smile. Soon after her death, as her photograph was flashed across the country in the television news channels, that smile came across to her friends in a bizarre, last, farewell.

Papiya Ghosh was killed by intruders, in her sprawling home, on the night of December 3, 2006, along with Malathi, the domestic help who had stayed with the family for over five decades. So why was she killed, this woman of countless friends? The highly premeditated nature of the crime, as also its brutal and efficient execution, raise many disturbing hypotheses about its source. Of course, this is hardly the occasion to ponder on the universal nature of crime. One can only engage with the specificity of this situation, where a woman who represented achievement and affluence, and above all exuded independence, and perhaps a certain defiance, lived alone. The broader situation of course is that of a deep rot in a governance system that has lost all justifiable claim to govern, except that which stems from the inertia of citizens. The physical vulnerability of women -regardless of class or other defining factors – is once again underlined by the type of political institutional context that frames our lives. The link between the personal and the political, so ably argued in Papiya’s research, was so tragically acted out in her own life. This politics is not only that of a failing state, but also perhaps of an emerging political economy that not only generates greed but legitimises it in all forms.

As our stunned anguish slowly gives way to anger, frustration and a variety of emotions, perhaps it is that link between the personal and the political that we again have to make, as members of the academic community. Again, to quote one of the many touching messages that have come in through the internet, mourning her loss, “for all the afternoons we spent together talking of so many things, Papiya, this was no way for you to go”. But, the writer goes on to say, that perhaps it was, perhaps this is one way in which Papiya would galvanise us into action. .